Gaining familiarity with the legal-citation practices used to document legal works may be impractical for student writers and sometimes even for scholars working in nonlegal fields. Nonspecialists can use MLA style to cite legal sources in one of two ways: strict adherence to the MLA format template or a hybrid method incorporating the standard legal citation into the works-cited-list entry. In either case, titles of legal works should be standardized in your prose and list of works cited according to the guidelines below.

Legal Style

Legal publications have traditionally followed the style set forth in the Harvard Law Review Association’s Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation, although some law reviews, such as the University of Chicago Law Review, have published their own style manuals. A more streamlined version of the Bluebook’s legal-citation method, the ALWD Guide to Legal Citation, was introduced in 2000. The Legal Information Institute, a nonprofit associated with Cornell Law School, publishes an online guide to legal citation geared toward practitioners and nonspecialists instead of academics.

Those working in law are introduced to the conventions of legal citation during their professional training. Legal style is a highly complex shorthand code with specialized terminology that helps legal scholars and lawyers cite legal sources succinctly. It points specialists to the authoritative publication containing the legal opinion or law, regardless of the version the writer consulted.

MLA Style

Students and scholars working outside the legal profession and using MLA style should follow the MLA format template to cite laws, public documents, court cases, and other related material. Familiarize yourself with the guidelines in the MLA Handbook, sections 5.17–22, for corporate authors and government authors.

Following one of the fundamental principles of MLA style, writers citing legal works should document the version of the work they consult—not the canonical version of the law, as in legal style. As with any source in MLA style, how you document it will generally depend on the information provided by the version of the source you consulted.

Titles pose the greatest challenge to citing legal works in MLA style. Since MLA style keys references in the text to a list of works cited (unlike court filings, which cite works in the text of the brief, or academic legal writings, which cite works in footnotes ), writers should, with a few exceptions (noted below), standardize titles of legal sources in their prose and list of works cited. Following the MLA Handbook, italicize the names of court cases (70):

Marbury v. Madison

When you cite laws, acts, and political documents, capitalize their names like titles and set them in roman font (69):

Law of the Sea Treaty

Civil Rights Act

Code of Federal Regulations

When a legal source is contained within another work—for example, when the United States Code appears on a website that has a separate title—follow the MLA Handbook and treat the source as an independent publication (27). That is, style the title just as you would in prose—in italics if it is the name of a court case, in roman if it is a law or similar document; even though the legal source appears within a larger work, do not insert quotation marks around the title:

United States Code. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text.

For more on titles in legal citations in MLA style, see “Tips on Titles,” below.

Commonly Cited Sources

A few examples of using MLA style for commonly cited legal sources follow.

- United States Supreme Court Decisions

- United States Supreme Court Dissenting Opinions

- Federal Statutes (United States Code)

- Public Laws

- Federal Appeals Court Decisions

- Federal Bills

- Hearings

- Executive Orders

- State Court of Appeals, Unpublished Decisions

- State Senate Bills

- Constitutions

- Treaties

- International Governing Bodies

United States Supreme Court Decisions

Where you read the opinion of a United States Supreme Court decision will dictate how you cite it in MLA style. Legal-citation style, in contrast, points to the opinion published in the United States Reports, the authoritative legal source for the United States Supreme Court’s decisions, and cites the elements of that publication.

For example, the case Brown v. Board of Education is commonly abbreviated “347 U.S. 483” in legal citations: 347 is the volume number of United States Reports; “U.S.” indicates that the opinion is found in United States Reports, which is the official reporter of the Supreme Court and indicates the opinion’s provenance; and the first page number of the decision is 483. (The American Bar Association has published a useful and concise overview of the components of a Supreme Court opinion.)

Regardless of the version you consult, you must understand a few basic things about the source: that it was written by a member of the United States Supreme Court on behalf of the majority and that, when you cite the opinion, the date on which the case was decided is the only date necessary to provide.

Following are examples of works-cited-list entries in MLA style for Brown v. Board of Education. The entries differ depending on whether the information was found on the Legal Information Institute website, published by Cornell University Law School, or on the Library of Congress website.

Legal Information Institute

The works-cited-list entry includes

- the government entity as author

- the name of the case (“Title of source” element)

- the year of the decision; it would also not be incorrect to include the day and month if it appears in your source

- the title of the website containing the case (“Title of container” element)

- the publisher of the website

- the website’s URL (“Location” element)

United States, Supreme Court. Brown v. Board of Education. 17 May 1954. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/347/483.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress site allows researchers to link to or download a PDF of the opinion from the United States Reports. To locate the case, the researcher must know the volume number of the United States Reports in which Brown v. Board of Education was published. A works-cited-list entry in MLA style would include the author (the government entity) and the title of the case, as well as the following information for container 1:

- United States Reports (“Title of container” element)

- vol. 347 (“Number” element)

- the date of the decision (“Publication date” element)

- page range (“Location” element)

Container 2 includes the name of the website publishing the case and its location, the URL. The publisher of the site is omitted since its name is the same as that of the site.

United States, Supreme Court. Brown v. Board of Education. United States Reports, vol. 347, 17 May 1954, pp. 483-97. Library of Congress, tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep347/usrep347483/usrep347483.pdf.

United States Supreme Court Dissenting Opinions

Sometimes, Supreme Court justices write dissenting opinions that accompany the published majority opinion. They are part of the legal record but not part of the holding—that is, the court’s ruling. If you cite only the dissent, you can treat it as the work you are citing:

Ginsburg, Ruth Bader. Dissenting opinion. Lilly Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. United States Reports, vol. 550, 29 May 2007, pp. 643-61. Supreme Court of the United States, www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/boundvolumes/550bv.pdf.

Federal Statutes (United States Code)

In MLA style, it will generally be clearest to create an entry for the United States Code in its entirety and cite the title and section number in the text, especially if you are referring to more than one section of the code.

If an online search directs you to the web page for a specific section of the United States Code, it would not be incorrect to cite the page for that section alone. For example, if you want to use MLA style to document title 17, section 304, of the United States Code—commonly abbreviated 17 U.S.C. § 304 in legal citations—title 17 can be treated as the work and thus placed in the “Title of source” slot on the MLA template, or if you cite the United States Code in its entirety, title 17 can be placed in the “Number” slot.

Your entry will once again depend on the version you consult. Below are examples from various websites.

website for the United States Code

On the website for the United States Code, you would likely determine that the United States House of Representatives is the author of the code. The United States Code is the title of the source, and since the source constitutes the entire website, no container needs to be specified: the source is self-contained, like a book (see p. 34 of the MLA Handbook). The site lists the Office of the Law Revision Counsel as publisher, so you would include that name in the “Publisher” slot, followed by the date on which the code was last updated, and the URL as the location:

United States, Congress, House. United States Code. Office of the Law Revision Counsel, 14 Jan. 2017, uscode.house.gov.

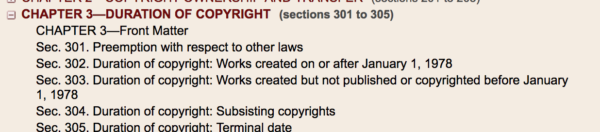

The body of your text or your in-text reference must mention title 17 and section 304 so the reader can locate the information you cite. It would not be wrong to include chapter 3 as well (title 17, ch. 3, sec. 304), although a discerning researcher will note that section numbers (304) incorporate chapter numbers (3), making “chapter 3” unnecessary to include.

If you do not include title 17 and section 304 in the text, you must include that information in the works-cited-list entry:

United States, Congress, House. United States Code. Title 17, section 304, Office of the Law Revision Counsel, 14 Jan. 2017, uscode.house.gov.

Legal Information Institute

A nonspecialist would not be able to determine from the Legal Information Institute site that the United States House of Representatives is the author of the United States Code. A basic citation would include the title of the code as displayed on the site, the title of the website as the title of the container, the publisher of the website, and the location:

United States Code. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text.

Government Publishing Office website

The website of the Government Publishing Office (variously referred to as the Government Printing Office) displays each statute heading (or “title”) as a web page:

You can treat title 17 as the work and the United States Code as the title of the container, as follows:

Title 17. United States Code, U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2011, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title17/html/USCODE-2011-title17.htm.

Or you can treat the United States Code as the title of the source and title 17 as a numbered section within the code, by placing title 17 in the “Number” slot on the MLA template:

United States Code. Title 17, U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2011, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title17/html/USCODE-2011-title17.htm.

Below are examples of how to cite other common legal sources in MLA style.

Public Laws

United States, Congress. Public Law 111-122. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 123, 2009, pp. 3480-82. U.S. Government Publishing Office, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-123/pdf/STATUTE-123.pdf.

Federal Appeals Court Decisions

United States, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Moss v. Colvin. Docket no. 15-2272, 9 Jan. 2017. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, www.ca2.uscourts.gov/decisions.html. PDF download.

It is customary to title court cases by using the last name of the first party on each side of the v. You may also wish to shorten a long URL, as we have done here.

Federal Bills

United States, Congress, House. Improving Broadband Access for Veterans Act of 2016. Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/6394/text. 114th Congress, 2nd session, House Resolution 6394, passed 6 Dec. 2016.

Hearings

United States, Congress, House, Committee on Education and Labor. The Future of Learning: How Technology Is Transforming Public Schools. U.S. Government Publishing Office, 16 June 2009, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg50208/html/CHRG-111hhrg50208.htm. Text transcription of hearing.

Executive Orders

After a president signs an executive order, the Office of the Federal Register gives it a number. It is then printed in the Federal Register and compiled in the Code of Federal Regulations. Executive orders usually also appear as press releases on the White House website upon signing.

United States, Executive Office of the President [Barack Obama]. Executive order 13717: Establishing a Federal Earthquake Risk Management Standard. 2 Feb. 2016. Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 24, 5 Feb. 2016, pp. 6405-10, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-02-05/pdf/2016-02475.pdf.

State Court of Appeals, Unpublished Decisions

Minnesota State, Court of Appeals. Minnesota v. McArthur. 28 Sept. 1999, mn.gov/law-library-stat/archive//ctapun/9909/502.htm. Unpublished opinion.

State Senate Bills

Wisconsin State, Legislature. Senate Bill 5. Wisconsin State Legislature, 20 Jan. 2017, docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2017/related/proposals/sb5.

Constitutions

If a constitution is published in a named edition, treat it like the title of a book:

The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription. National Archives, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 28 Feb. 2017, www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript.

The Constitution of the United States, with Case Summaries. Edited by Edward Conrad Smith, 9th ed., Barnes and Noble Books, 1972.

References to the United States Constitution in your prose should follow the usual styling of titles of laws:

the Constitution

But your in-text reference should key readers to the appropriate entry:

(Constitution of the United States, with Case Summaries)

If the title does not indicate the country of origin, specify it in the entry:

France. Le constitution. 4 Oct. 1958. Legifrance, www.legifrance.gouv.fr/Droit-francais/Constitution/Constitution-du-4-octobre-1958.

Treaties

Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. United Nations, 1998, nfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf. Multilateral treaty.

United States, Senate. Beijing Treaty on Audiovisual Performances. Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/114/cdoc/tdoc8/CDOC-114tdoc8.pdf. Treaty between the United States and the People’s Republic of China.

International Governing Bodies

Swiss Confederation. Bundesverfassung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft. 18 Apr. 1999. Der Bundesrat, 1 Jan. 2016, www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19995395/index.html.

United Nations, General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Resolution 217 A, 10 Dec. 1948. United Nations, www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/. PDF download.

Writing for Specialists: A Hybrid Method

A writer using MLA style to document a legal work for a specialized readership that is likely to be familiar with the conventions of legal documentation may wish to adopt a hybrid method: in place of the author and title elements on the MLA format template, identify the work by using the Bluebook citation. Then, follow the MLA format template to list publication information for the version of the source you consulted.

For example, to cite the United States Code using the hybrid method, treat the section cited as the work. As above, you can omit the title of the website, United States Code, since the code constitutes the entire website and is thus a self-contained work.

17 U.S.C. § 304. Office of Law Revision Counsel, 14 Jan. 2017, uscode.house.gov.

If you are citing a court case, begin the entry with the title of the case before listing the Bluebook citation. In the hybrid style, cite Brown v. Board of Education as found on the Legal Information Institute website thus:

Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/347/483.

Other sources (public laws, federal appeals court decisions, etc.) can be handled similarly.

If using the hybrid method, do not follow the handbook’s recommendation to alphabetize works that start with a number as if the number is spelled out. Instead, list works beginning with numbers before the first lettered entry and order numbered works numerically.

TIPS ON TITLES

Styling titles when you document legal sources in MLA style may be challenging. Below are some guidelines.

- Standardize titles of legal sources in your prose unless you refer to the published version: as the MLA Handbook indicates, italicize the names of court cases, but capitalize the names of laws, acts, and political documents like titles and set them in roman font.

- When a legal source is contained within another work—for example, when the United States Code appears on a website with another title—follow the MLA Handbook, page 27, and treat the work as an independent publication. That is, style the title just as you would in prose—in italics if it is the name of a court case, in roman if it is a law or similar document; even though the legal source appears in a larger work, do not insert quotation marks around the title.

- In the names of court cases, use the abbreviation v. consistently, regardless of which abbreviation is used in the version of the work you are citing.

- To determine the name of a court case, use only the name of the first party that appears on either side of “v.” or “vs.” in your source; if the name is a personal name, use only the surname.

To shorten the name of a court case in your prose after introducing it in full or in parenthetical references, use the name of the first-listed nongovernmental party. Thus, the case NLRB v. Yeshiva University becomes Yeshiva. If your list of works cited includes more than one case beginning with the same governmental party, list entries under the governmental party but alphabetize them by the first nongovernmental party:

NLRB v. Brown University

NLRB v. Yeshiva University

Refer to the nongovernmental party in your prose and parenthetical reference, alerting readers to this system of ordering in a note.

NOTE

Special thanks to Noah Kupferberg, of Brooklyn Law School, for assistance with these guidelines.

36 Comments

Laurie Nebeker 08 August 2017 AT 02:08 PM

My eleventh-grade English students write research papers about Supreme Court cases. In the MLA 7th edition (5.7.14) there was a note about italicizing case titles in the text but not in the list of works cited or in parenthetical references. Has this changed for the 8th edition? Also, you've given examples about formatting SCOTUS rulings, but most of the resources my students use are articles about the cases from news sources, specialty encyclopedias, etc. Should case titles be italicized when they appear within article titles? Thanks!

Angela Gibson 09 August 2017 AT 07:08 AM

You are correct to note this change. To make legal works a bit easier to cite, we now recommend that writers italicize the names of court cases both in the text and the list of works cited. When the name of a court case is contained within another work, style the title just as you would anywhere else. Thus, a SCOTUS ruling in the title of a news article would appear in italics. Thanks for reading; I hope this helps!

Nia Alexander 31 January 2018 AT 06:01 PM

How would I cite the 2015 National Content Report? It contains information similar to that of a census.

Angela Gibson 01 February 2018 AT 07:02 AM

There is an example here: https://style.mla.org/citing-tables/.

Nathan Hoepner 12 February 2018 AT 01:02 AM

One of my students wants to use the Versailles Treaty (officially, "Treaty of Peace with Germany"). The Library of Congress has a pdf copy posted. Should he list the treaty in his sources with the URL, or, since is just a copy of the official treaty, just list title, date, and "multilateral treaty"?

ben zuk 17 March 2018 AT 06:03 PM

how would I cite Supreme Court case from Justia?

Patricia Morris 27 March 2018 AT 10:03 AM

Can you give an example for citing the Occupational Outlook Handbook, published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics?

Michael Park 03 May 2018 AT 12:05 PM

How do i cite a introduced bill into congress

ML Chilson 04 November 2018 AT 05:11 PM

How do I cite a pending case that is still at the trial court level, including citation to the briefs that have been filed by the various parties?

Blah 08 November 2018 AT 11:11 AM

how do you cite a complaint in mla format

Marlow Chapman 10 December 2018 AT 08:12 PM

How would one cite a Title (specifically Title VII) from the Civil Rights Act of 1964?

Angela Gibson 11 December 2018 AT 05:12 PM

How you cite it will depend on where you access it. Some points: following the MLA format template, your entry will start with the title of the law. This will either be Civil Rights Act or Title 7 (see the discussion of Federal Statutes above for considerations about which title to begin your entry with). Your in-text citation (whether in prose or parentheses) should direct the reader to the first element in your works-cited list (in other words, the title).

Jeff Jeskie 04 February 2019 AT 08:02 AM

How do my students properly list the Supreme Court cases that are linked on the Exploring Constitutional Law site by Doug LInder at UMKC Law School site?

http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/home.html?

Patricia Moseley 14 February 2019 AT 10:02 AM

I need help. My 8th grade history class is answering questions on the US Constitution and citing their answer.

There are five rights in the First Amendment, which include freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to peaceably assemble, and the right to petition the government for a redress of their grievances (U.S. Constitution).

Is this in-text citation done correctly? Also, are the amendments spell out or does one use the Roman numeral in text?

Thank You!!!

Angela Gibson 15 February 2019 AT 10:02 AM

If U.S. Constitution is the first element in the works-cited-list entry, the in-text citation is correct. Spell out ordinal numbers (First Amendment), but use numerals for numbers of count (Amendment V) and, by convention, use Roman numerals for divisions of legal works that use them.

Ella 05 December 2019 AT 08:12 PM

How would you cite a state supreme court case?

Ana 06 December 2019 AT 09:12 AM

How would I cite an Act? More precisely, I want to cite The New York State Dignity for All Students Act. How would I do it on in-text citations and on the work cited page? Thanks!

Amanda 17 April 2020 AT 05:04 PM

How would I cite a tribal constitution?

Do I use the date of the original publication or the most recent amendment or resolution?

most are found on their tribal government websites so would i treat it like this:

(italicized) Title of Document: Subtitle if Given (italicized) . Edition if given and is not first edition, Name of Government Department, Agency or Committee, Publication Date, URL. Accessed Day Month Year site was visited.

yet, I still do not know what date to use.

Or should i just cite it from a print publication or Nat. Archives so I can use the example given in your list above?

Angela Gibson 20 April 2020 AT 09:04 AM

Cite the version you're looking at and use the date of access if it's the only date you can provide.

Marissa 25 October 2020 AT 05:10 PM

How would you cite The Declaration of Independence?

Jennifer A. Rappaport 26 October 2020 AT 08:10 PM

Thanks for your question. Please consult Ask the MLA: https://style.mla.org/category/ask-the-mla/

Carol Holyoke 19 January 2021 AT 10:01 PM

Could you please tell me how to cite the Declaration of Independence? Do I put it in the Works Cited List?

Angela Gibson 20 January 2021 AT 09:01 AM

It is generally a good idea to create a works-cited-list entry for the version of the document you are transcribing a quotation from (e.g., see our example for the Constitution). Create your entry just as you would for any other source--follow the template of core elements and list any relevant elements that apply.

Diane 23 February 2021 AT 07:02 PM

How do I correctly cite a Congressional public law In Text? I can only find how to cite in works cited pages. Thank you!

Rowena 28 April 2021 AT 09:04 AM

If I quote sections from a piece of legislation does it need to be italicised as well as quotation marks?

Charlotte Norcross 15 November 2021 AT 11:11 AM

How do I correctly cite the congressional record from a specific session? Thanks!

Carl Sandler 02 February 2022 AT 02:02 PM

I am submitting a report to an attorney consisting of investigative findings related to an automobile accident. Some of the information in my report will be technical in nature and other information will be in the form of my opinion(s) based on conclusions drawn from deposition testimony of witnesses and persons knowledgeable of the event.

Considering the report will be read by both legal professionals and others not of the legal profession, what approach and format (with examples, please) should be used to cite deposition testimony and also Exhibits presented during the taking of the deposition? I am familiar with Bluebook style of legal citations, however not all persons reading my report would have this same understanding.

Lev 18 April 2022 AT 11:04 AM

Dear MLA Editor: When citing court cases in another language (French), should I keep the title of the case in the original language, translate it, or provide a translation in brackets? The same question goes for the name of the docket number, court, date of publication, and other elements. The MLA manual does not offer any guidance on this! Thanks in advance for any help.

Heidi 27 April 2023 AT 10:04 AM

What is the proper way to reference a recently filed lawsuit (a pending case) in legal writing (letters and memos)? Thanks!

Jennifer Washington 13 February 2024 AT 11:02 PM

How are state educational codes shaping standards for textbooks and materials cited in-text and on works cited?

Margaret Handrow 09 April 2024 AT 09:04 AM

How are state laws and state house bills cited? What would be the in-text citations for state laws and state house bills?

Laura Kiernan 09 April 2024 AT 03:04 PM

For guidance on citing state laws, see this post on the Style Center.

Margaret Handrow 11 April 2024 AT 08:04 PM

The Works Cited for state laws I have. What do the parenthetical and narrative in-text citations look like?

Margaret Handrow 11 April 2024 AT 09:04 PM

MLA Handbook 6.6 has the following example for in-text citations for U.S. Supreme Court cases - A recent case held that "the immunity enjoyed by foreign governments is a general rather than specific reference" (United States, Supreme Court).

How does MLA handle more than one court case? For example:

United States, Supreme Court. Ableman v. Booth. United States Reports, vol. 62, 7 March 1859, pp. 506-525 Range. Fastcase, https://public.fastcase.com/jaEE2PXzRXmZ99jOLMt1Il18sGeib03xlSTGPHuTkMPJngvbMveRhemGzelvNShH. [62 US 506]

and

United States, Supreme Court. Miles v. United States. United States Reports, vol. 103, October Term, 1880, pp. 304-316 Range. Fastcase, https://public.fastcase.com/waZtJvSA54UAurM2rmIZz8tSNJfRFb72tc2JnYR%2b1g3S9cDguTf04pkUdcNTnFEq [103 US 304]

Would the following work as parenthetical in-text citations?

(United States, Supreme Court, Ableman v. Booth 520) and (United States, Supreme Court, Miles v. United States 311)? Or would using (Ableman v. Booth 520) and (Miles v. United States 311) be better?

Margaret Handrow 11 April 2024 AT 09:04 PM

Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), for example - 28 CFR Part 551 Subpart G.

My best guess for the Works Cited would be something along this line - United States. Department of Justice. Bureau of Prisons. Department of Justice Institutional Management. “Miscellaneous, Administering of Polygraph Test, Purpose and Scope, Procedures,” Title 28, 29 June 1979, Part 551, Subpart G, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-28/chapter-V/subchapter-C/part-551/subpart-G?toc=1.

Would the parenthetical in-text citation be - (United States. Department of Justice. Bureau of Prisons. Department of Justice Institutional Management 551)? This is for one source from 28 CFR Part 551 Subpart G. How would one differentiate a different Subpart that is on the same page?

Mustafa 15 May 2024 AT 10:05 AM

How do I cite a case a court case transcript? Like the Israel Vs South Africa "Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip" Case?

Join the Conversation

We invite you to comment on this post and exchange ideas with other site visitors. Comments are moderated and subject to terms of service.

If you have a question for the MLA's editors, submit it to Ask the MLA!